Everything You Need to Know: Is that a berry?

Cucumbers aren’t vegetables, and neither are bell peppers. Raspberries are fruit, but they aren’t berries, and neither are blackberries. But pumpkins, oranges, and bananas are all berries. What’s the story here, and how can you figure out what’s what in your kitchen? Read on for answers in this edition of Everything You Need to Know About…

The study of plant biology is called botany. Though botanists do everything from experiments on plant molecular genetic to computer modeling of ecological interactions in huge forests, there’s a lot of botanizing to be done right around your own home — even, as you’ll see today, in your own kitchen. No matter where you live, plants are an integral part of your life in one way or another, and it’s worth learning more about these amazing organisms.

Is that a vegetable?

Watch the video for this section here!

You may have heard the argument that a tomato is a fruit, even though you likely think of it as a vegetable. But did you know that green beans are also fruits? So are peppers, pumpkins, and cucumbers. However, many things you think of as vegetables — such as spinach, celery, and carrots — really are vegetables. So, what’s the difference? And why should you care? The answer lies in plant development.

Plants have three basic organs: roots, stems, and leaves. In general, botanists don’t think of structures like pinecones or flowers as distinct organs; we have good evidence that these reproductive structures evolved from leaves. Of course, this doesn’t mean that cones and flowers aren’t important! In fact, life as we know it today hinges heavily on the evolution of flowers (more on cones later): Almost (but not quite) every plant humans eat — and have eaten throughout our collective history as a species — is a flowering plant. In fact, many of the things we eat develop from flowers themselves, and therein lies the key distinction between fruits and vegetables.

Botanically speaking, fruits are specifically structures that develop from flowers; “vegetable” is a very broad and nonspecific category, but generally includes any plant part humans eat which doesn’t develop from a flower. A handy trick to tell the two apart in your kitchen: If an item of produce has seeds, it’s probably a fruit. If it doesn’t have seeds, it’s probably a vegetable. Seeds are tiny plant embryos packaged up with some nutrients for sprouting (a seedling will need this supply of energy to survive until it makes photosynthetic leaves) and a protective cover.

In angiosperms (flowering plants), seeds develop when sperm cells contained within a pollen grain fertilize an egg cell contained within an ovule; the ovule is in turn contained within an ovary, and the ovary often (but not always) develops into a fruit around the seed(s). Taken together, we call an ovary, the ovules, and the structures around them that contribute directly to fruit formation a carpel (you may see the term “pistil” used here too). A flower can have multiple carpels or just one; in either case, all the reproductive parts of a flower involved in seed-bearing taken together are the gynoecium. The parts of a flower that directly contribute to making pollen (filaments and anthers) are called stamens; all the stamens taken together are the androecium. Flowers often have both a gynoecium and an androecium, but after pollen lands on the flower and an egg cell is fertilized, only the gynoecium contributes to fruit formation.

Is that a berry?

Watch the video for this section here!

Now that we’ve sorted our vegetables from our fruits, we arrive at another surprisingly interesting question: Is that a berry? Botanists have specific (if sometimes difficult-to-apply) definitions for different types of fruits, and these don’t always align with culinary expectations. As you probably noticed in the video above, many things you probably think of as berries — such as strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries — are not, botanically speaking, berries. However, some fruits you may not have suspected — such as bananas, cucumbers, and pumpkins — are true berries (and blueberries really are berries; botanists aren’t here to ruin everything).

First, let’s make a couple broad divisions: As noted above, most fruits develop from the ovary, which is one of the female reproductive structures of a flower. Fruits which do not develop from the ovary generally develop from non-reproductive structures near the ovary; we call these accessory fruits. The portion of an apple that you eat, for instance, develops from a part of the flower called the hypanthium (aka “floral cup”). Berries, by definition, develop from the ovary (i.e., they are not accessory fruits). This rules out strawberries, the juicy red part of which develops from the receptacle (the thick part of the stem just before a flower). The little yellowish-green structures you probably think of as strawberry “seeds” are actually individual fruits! These hard, dry achenes each contain a single tiny seed.

Another broad set of categories: Some fruits develop from a single carpel of a single flower, but others are a conglomeration of different carpels within a single flower (forming an aggregate fruit), and yet others develop when carpels of different flowers fuse together (forming a multiple fruit). Botanists don’t consider aggregate or multiple fruits for potential berryhood; this rules out blackberries and raspberries, which are both aggregate fruits (and strawberries again; someone really should’ve consulted a botanist before naming those things). In case you were wondering, you likely don’t see as many multiple fruits in your day-to-day culinary adventures, but pineapples are a classic example.

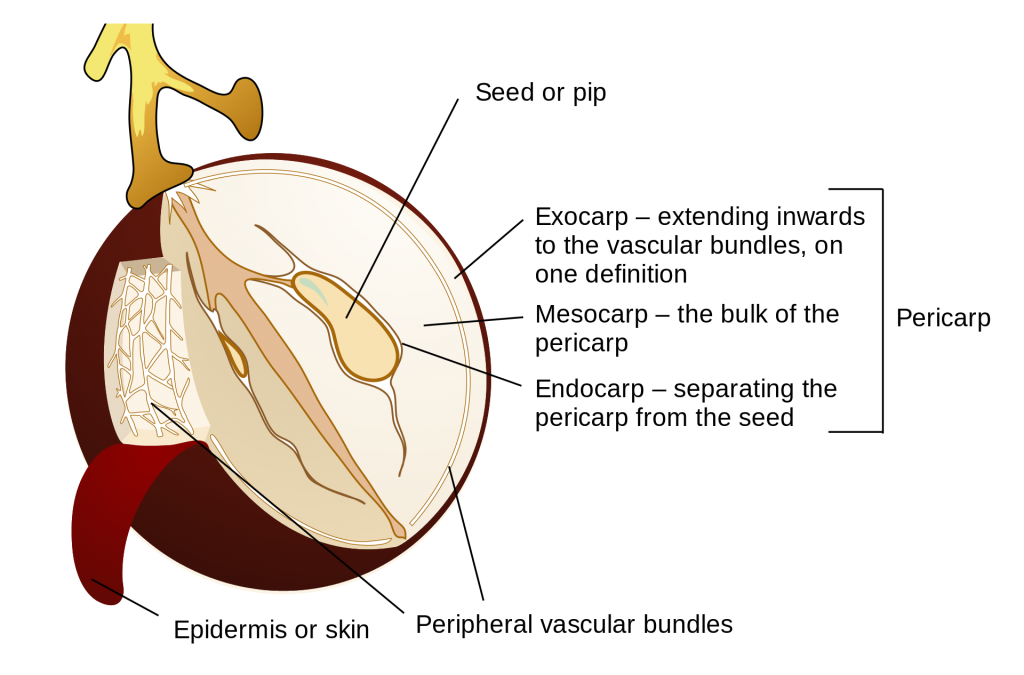

One last division to point out: Some otherwise-fleshy fruits contain hard “stones” or “pits” that develop from inner layers of the ovary (the endocarp) and protect a single seed within. We call these types of fruits drupes; peaches and plums are drupes. By definition, you won’t find a stone or pit in a true berry. Some berries do carry a solitary seed, but it is not covered in toughened endocarp (and, more often, berries contain many seeds). Blackberries, though we’ve already disqualified them under the “no aggregate or multiple fruit” clause, are also out on this count. Each tiny, round compartment of a blackberry contains a tiny pit — in botanical terms, a blackberry is an aggregate of drupelets.

A final note before we move on: All the fruits we’ve discussed so far are indehiscent — they do not dry out and split apart at maturity to release their seeds. Green beans, and indeed legumes generally, do dry out and dehisce (split apart) when the seeds within are mature. Some fruits do dry out, but do not dehisce, at maturity; nuts fall into this category. Berries do not dry out or split apart at maturity.

Now, at this point, we’ve ruled out apples, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, pineapples, peaches, and plums. But blueberries, pumpkins, oranges, and bananas all are berries. What unites these fruits in berryhood? Mostly, lack of any of the aforementioned traits. As noted previously, berries develop from one carpel of one flower. However, the ovary giving rise to a berry may be divided into locules (fused carpels); this is how berries such as tomatoes, which contain a number of internal chambers, develop. Berries often have many seeds, which develop from numerous ovules within the single ovary, but a berry could have just one seed. The wall of the ovary in a flower that’s making a berry typically develops into three soft layers — endocarp, mesocarp, and exocarp — around the seeds. In one special group of berries (the pepos), which includes pumpkins, cucumbers, zucchini, and watermelons, the exocarp becomes leathery and sometimes quite thick. In another special group (the hesperidia), which includes oranges, lemons, and limes, you’ll find a tough rind surrounding an edible interior full of juice sacs.

Watch the summary video here!

Wait... What is that?

Now, one final twist: You’ve likely seen bluish juniper berries or bright-red yew berries at some point. However, neither of these are true berries. Indeed, they’re more like pinecones than they are like any type of fruit! Both juniper “berries” and yew “berries” are mature ovulate (seed-containing) cones of different species of gymnosperms. We learned the phrase “angiosperm” (flowering plant) earlier; the roots of this word mean “vessel seed”. The seeds of angiosperms are protected, and their dispersal is aided, by fruits, which develop from flowers. “Gymnosperm”, on the other hand, means “naked seed”. Though the seeds of gymnosperms may form on a unique reproductive structure (such as a pinecone), gymnosperms do not make flowers, and thus do not make fruits.

The gymnosperm lineage differentiated substantially earlier than the angiosperm lineage in the plant evolutionary timeline, but it’s important not to think of gymnosperm taxa as “lower” or “less advanced”. Gymnosperms are still here with us today, just like angiosperms, and are critical to ecosystems around the world. Gymnosperms have intriguing life histories and morphologies of their own, and are very much worth learning more about! (And both lineages of seed plants diverged well after groups of plants that don’t make any seeds at all, such as mosses, hornworts, liverworts, and ferns; all of these groups are also fascinating in their own ways.)

A few interesting asides

Watch our bonus video, What is an apple?, here!

It does a plant no good for you — or any other animal — to pull off and eat its leaves (but vegetables are good for you and most plants can just make more leaves; please eat them nonetheless). However, it is generally helpful for plants if animals eat its fruit. Dispersing seeds away from the parent plant is critical for many angiosperms; spreading offspring far and wide increases the odds that at least a few of them will survive, and very few of them will compete with the parent for resources such as water and sunlight.

Avocados are an interesting problem-fruit. They are most classically defined as berries, since the hardened segment of endocarp isn’t thick enough to qualify for drupe status. However, avocados do have a hardened endocarp, and some argue that they should be classified as drupes.

Image credits

“Diagram of flower parts” by Mariana Ruiz LadyofHats -own work. Public domain. Available from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flower#/media/File:Mature_flower_diagram.svg

“Blackberries in a range of ripeness, in West Hartford, Connecticut” by Ragesoss – own work. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0. Available from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackberry#/media/File:Ripe,_ripening,_and_green_blackberries.jpg

“Diagram of a grape berry, showing the pericarp and its layers” by LadyofHats. Cropped and re-labeled by Peter coxhead. Used under CC BY-SA 4.0. Available from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berry_%28botany%29#/media/File:Grape_berry_diagram_en.svg

Image of juniper leaves and mature ovulate cones is the author’s own work.